I feel that claims that Irish clothing

changed very little over time are completely false. A 4th century Irishman did not

wear the same thing as 10th, who didn’t wear the same as 14th,

which certainly wasn’t the same as the 16th—which is what I will

cover in this article.

There

are common elements throughout—such as the leine

gel, the white or saffron dyed linen shirt; the wearing of the Irish Brat,

or large, fringed, cloak—a garment which seems to have been truly omnipresent[1];

and the predilection to wearing tight, or no pants. In addition to the Irish styles of dress,

English and Continental fashions were also slowly adopted (often with the

addition of the brat), and were more prevalent in major cities (particularly

port cities), among the upper class, and later in the century.

Throughout

this period the English rulers (Henry VIII…) attempted to enforce freshly

created laws forbidding Irish modes of fashion, and haircuts—this is one of our

prime sources on the essentials of Irish clothing. Articles targeted were the glib hairstyle,

women’s headwear, the dying with saffron, the

amount of cloth used in the leine, and ,particularly, the Irish Mantle

(with its fringe).

Men’s

Clothing

Leine: This (in various forms), along with the brat,

was one of the two main articles of Irish dress throughout the ages. The leine was invariably made of linen,

likely a heavier weight, tightly woven type than is commonly available

today. The colour by this time was almost

invariably saffron dyed yellow (a bright yellow)--or natural for the destitute.

The leine was usually long—ankle

length—and bloused over the belt in order to pull it up to knee level and allow

greater freedom of movement. Necklines

seem to have been roughly ‘V’ shaped and often fairly deep. I believe that they were probably rounded in

the back, making the neck opening a loose teardrop shape when laid out flat

during construction.

The sleeves of the leine were very

wide at the cuff, often hanging to the knee—but were narrow at the top[i]. An interesting evolution on these is that

though the sleeve itself is very wide at the cuff—they were not necessarily

very long. Several images show the

sleeve stopping just below the elbow, presumably to give greater freedom of

movement and reduce the chance of entanglement I believe that at least occasionally

the sleeves were full length, and in the “bagpipe sleeve” style.

There were NO pleats on the sleeves—do

not even think about it, much less use a sleeve with drawstrings in it. This is a renfairism, dating to the

1960s-70s.

In 1541 an act was passed to try to

limit the amount of fabric that went into a leine—previous to that Henry VIII

tried to pass a law limiting them to seven yards (the yard measure was then, as

now, 36 inches), in 1539[ii]. The amounts given as allowable ranged from 10

cubits for a laborer, to 20 cubits for a nobleman, with a kern being allowed

16. These are 5.5, 11, and 8.8 yards,

respectively[2]. Remembering that the linen being woven at the

time was only 20-22 inches wide it could be quite doable to get 2.75-5.5 yards

of modern 45 inch material into the garment.

In Derricke’s Image of Ireland we see a completely different form of leine and

inar. After reading an article on the

subject[iii],

I agree with the author that those images were made by an engraver who was

going off of Derricke’s notes. Also,

there is the theory that the work Image

of Ireland was propaganda against the Irish—trying to make them look

foolish, and ripe for invasion. Another

thing is that the rest of the images are fairly close on what the clothing

looks like—it’s Image of Ireland that

is the anomaly. Looking further at one

of the woodcuts you can see that the sleeves appear to be only elbow length

(ish), are sewed partway up the opening (same as the Dutch watercolor), and

seem to have the bottom of the opening tied to the wrist.

Brat: The brat, or cloak[3],

is one of the iconic garments of the Irish (along with the leine). It was made of heavy wool, with a heavy

woolen fringe along the top edge similar to faux fur. The brat has been interpreted as being both

rectangular or semicircular[4],

and should be from the knee to ankle in length.

Interestingly they are often depicted in this period as being

ragged—this however may have been a form of social commentary, as we do not

have any illustrations from this period that were done by an Irishman. Another thought is that the bottom edge of

the brat could actually be dagged.

Interestingly, in the images we have of the brat being worn, there is no

evidence of a broach or pin holding it shut—it seems to just be draped over the

shoulders, and perhaps held shut with the hand.

In

Sir William Herbert’s letter to Lord Burghley (25 May, 1589) he says the

following about the brat.

“Eightlie, the mantle servinge vnto

the Irishe as to a hedghogge his skynne or to a snaile her shell for a garment

by daie, and a house by night it maketh

them with the Contynuall vse of it, more apt and able to lieu and lie out in bogges and woodes, where their

mantle serveth them for a matteras and a

bushe for a bedsteede, and thereby are lesse addicted to a loyall dutifull and Civill lieffe.”[iv]

The fringe is the most notable part of

the brat—it serves to keep the weather off your neck and even as a hood—it is

the thickest around the neck and runs down the front edge of the cloak. It has been stated that the fringe was

separate from the brat, and could be taken off (for political reasons)[v]—and

presumably recycled.

The fringe may be made by a couple of methods,

such as layers of wool fabric that has been unraveled; or by taking individual

wool yarns, passing them through the fabric and fastening them on the other

side—as though you were rug hooking[5]. Another option may be to use fringed or

tufted weaving or tablet weaving. The

color of the fringe could be either the same colour as the rest of the cloak,

or a contrasting/complementary one.

While the fringe was often wool, it was at least occasionally made of

silk threads for higher class wear[vi].

Another peculiarity of the Irish brat

was that it was at least occasionally made of a shaggy wool, a faux fur

resembling sheepskin or the pelt of a wolfhound. This is created during the weaving process by

inserting short lengths of woolen yarn or unspun wool between the warp threads

and packing the next weft thread onto it.

I would suspect that on the wrong side of the fabric the little bits of

wool fiber would be felted together to prevent your shags from pulling out. I do believe fringe could be woven into the

material the same way[6].

Inar

or Ionar: The inar is commonly referred to as the jacket

of the Irish. It was commonly made of

wool and seems to have been considered a surface for decoration (more on the decoration in a moment). As a garment, it is an optional outer layer.

The inar is extremely short and open

in front, with the main body only coming down to around the bottom of the

sternum and a pleated skirt below that reaches to the hips or waist. A fabric belt or band of trim holds it closed

and covers the seam between the skirts.

The sleeves on this jacket were also

peculiar—they had the bottom seam open for the length and were closed at the

wrist with a tie or button (or allowed to hang loose). This was of course to allow for the

voluminous sleeves of the leine.

Interestingly enough, in the above image you can clearly see that the

sleeve cap is off the shoulder and that the bottom opening is rotated slightly

to the front.

On the ornamentation of the inar, in

the images available, there appear to be two types with a third combining the decorative

elements of the other two. The first,

and more fancy are floral patterns in the form of stylized vines and the

occasional flower. The second are lines

of trim (contrasting strips of material) sewn on at even intervals—on the body

they may be either horizontal, or diagonal.

On the sleeve they appear always as horizontal, perpendicular to the

length of the sleeve. There is also one

example that has floral decorations on the body, and stripes on the sleeves[7]

(this is the third, combination style).

In

addition to this there are contrasting stripes, which can be interpreted[8]

as fabric bindings or facings, occasionally shown on the neckline and sleeve

openings. There may also have rarely

been slashing on the shoulders.

There is also a possibility that the

floral patterned inars are appliquéd with gilded leather. It is known (via contemporary description)

that the Irish did decorate with gilded leather, but on their quilted “jack”.[vii]

Trius: The pants of the Irish. They were uniformly tight fitting on the legs,

and likely had either stirrup straps running under the foot, or integral feet. Often they are depicted as being a simple

plaid or checked fabric, with the legs cut on the bias to allow stretch. See Extant Garments.

Headwear: Strangely enough, the Irish are usually depicted

without headwear. This may be because

they didn’t always wear hats, or could be a political commentary (by the

English) that they were barbaric—remembering that elsewhere at this time hats

were mandatory part of “civilized” dress.

It seems that for the most part the Irishman did not wear hats, as they have long hair--“this hair being

exceedingly long they have no use of cap or hat”[viii].

There are a few sketches of Irishmen

wearing hats—a low crowned hat with a broad brim, sometimes upturned; a beret

type that may have had feathers in it; and one of an archer with a pointy

skullcap type thing. I also have seen a

sugarloaf type hat in several cases.

Other

than the native headwear, caps and hats were also being imported from England,

with dramatic spike in volume in the last few decades of the 1500s. From the 1530s (at least, due to a law passed

requiring all males to wear English knit hats on Sundays) that variety, at

least, was commonly owned—if only in the cities.

There have been a couple of extant

finds of the broad hat. They were found

in a bog at Boulebane, near Roscrea, and are a yellowish brown colour (I believe that they may have been black originally, and were bleached by

action of the sun[9]). They are made of several pieces of thick wool

felt sewn together and have tags of wool approximately an inch long stitched

on.

In addition to the three found in

Boulebane, felt hats have also been found in bogs in Donegal, Mayo, and Sligo

counties. However, like many bog finds,

the actual dating could be problematic.

Hair:

Men’s

hairstyles seem to come in two varieties: Glibs and long locks; and the shaven

sides. There appears to be two

definitions of glibs[10]--either

curled and/or matted hair on the forehead (possibly covering the eyes), or long

locks. Edmund Spencer goes on and says

the glib was “A long curled bush of hair, hanging down over the eye…”[ix]

Broges: They don’t

seem to have changed much from earlier periods.

Several sources call them primitive and having a single layer of leather

for the sole, like the earlier, simple, bag/bog shoes. In A Discourse of Ireland (1620)

it says the following about footwear “His broges are single soled, more

rudely sewed than a shoo but more strong, sharp at the toe, and a flapp of

leather left at the heele to pull them on.”

Observations on Clothing in

Derricks Images of Ireland

While,

as I previously said, I do not feel that Derrick’s images were true to life, I

am adding notes on them into my article for the sake of completion.

Leine: It may be seen that all of the men’s

leinte have wide bagpipe sleeves (mostly elbow length), a front opening which

is not visible—meaning it is wide open, showing the musculature of the

chest—and a very wide, pleated hem, which barely reaches the thigh. The pleats appear to be focused at the sides

and back, with few to none at the front.

Brat: When it is

shown—which is far more seldom than the usual—it appears to be semi-circular,

and has the usual thick fringe. The

fringe in these cases appears to be on the inside, and only goes to the elbow

or so.

Inar: The inar in

Images of Ireland appear to have a rolled or shawl collar open to the sternum

or waist, tight sleeves—with an opening along the underside to allow the Leine

sleeve to fall through--, and a very short, heavily pleated skirt.

Occasionally, the images show slashes

running partway down the upper arm. In

addition, something which may be contrasting trim shows at the wrist and/or

elbow. As for the skirts of the inar,

they appear to almost be constructed like a neck ruff.

Trius: It is unknown

if the trius are shown in these images.

If they are, they are shown as skintight and were paid no special

attention by the artist.

Headwear: The Irish, other than the Chief—who is

wearing English clothing—are not depicted as wearing any headwear. Propaganda, remember.

Hair: Somewhat messy, no different from other

artists depictions (other than the occasional curling on the sides). A drooping mustache was worn, either with or

without a full beard—some of the Irish are shown as clean shaven.

Broges: No different than the expected, being of the

slipper type. It does appear that there

is a separate sole, which may or may not be true—the artist did show the side

seam in some cases.

Women’s

Clothing

There

is unfortunately not as much information on women’s clothing, as men’s. I would also like to apologize in advance for

the number of my speculations. The

essentials of the clothing is much the same—a wide sleeved leine, and a

brat. However they seem to be depicted

as wearing another, more modish (but still Irish), outer dress as well!

Leine: Once again, there is not very much

information on this garment. It was made of linen, either dyed saffron, or

white. To preserve modesty it was ankle

length, and had full sleeves. There is

one reference to the leine (called a chemise in the quote) being the only

garment worn, other than a cloak[x]. In The Description of Ireland by

Thomas Gainsford (writing in 1618), he says of the women of Ireland “Their

apparel is a mantle to sleep in, and that on the ground or some rushes or

flags: a thick gathered smock with wide sleeves graced with bracelets and

crucifixes about their necks:…”[xi]

Still

an iconic garment of the Irish, it is an ankle length ‘tunic’, ‘smock’, or

chemise type garment, sometimes with wide sleeves. Like the men’s version, it was of linen,

either saffron dyed, or white. However

the only illustration available of a lady wearing one, has ‘bagpipe’ sleeves,

trimmed with ruffles at the wrist.

In one of Derricke’s woodcuts, the

lady appears to be wearing a calf length leine, with elbow length pendulous

sleeves. Over this she’s wearing a waist

length jacket laced in front, with a rolled collar, tight sleeves (with the

leine sleeve hanging out), and an apron.

Brat: See the men’s section on the same garment, as

there is very little difference in the construction. To this I will add that there is a comment by

Luke Gernon (writing just out of period, in 1620) that their mantles were a

brown blue colour with like fringe, or light colours (green, red, and yellow

are mentioned) with fringes “diversified”[xii]. He goes on to say that the mantle is worth 4

pounds[xiii]

and that the brat was worn inside, as well as out. Dagging the edges may well be a possibility.

Gown: There is one extant Irish gown, to my

knowledge--from this period--, in the form on the Shinrone gown. There appear to be two major forms of dress—however,

it is reasonable to believe that the

ladies of the period would have copied dresses they were exposed to (i.e.

English), particularly the younger generation, and particularly in major

population centers (i.e. Dublin)[xiv].

Both forms appear to have long

waists, and are laced from the top of the breast to the waist. Necklines are shown in both rectangular

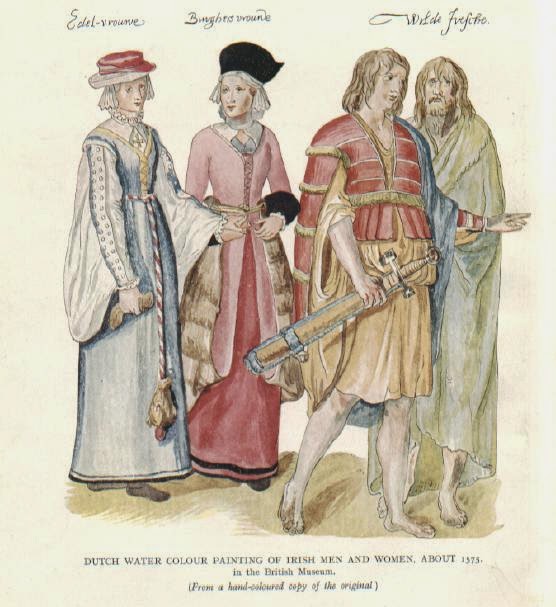

(Shinrone gown) and ‘V’ necked (Dutch watercolor) forms.

Sleeves appear in a conventional full

sleeve with a turned back cuff (this example is a fur lined, outer

gown)—obviously not worn with the wide sleeved leine, and just a narrow strip

of material running down the outer arm, and fastened at the wrist (which is

worn with the bagpipe sleeved leine mentioned above)—the later being the more

native form of dress. Interestingly

enough, the narrow form of dress sleeve is apparently decorated with silver

buttons, or bezants. This practice must

have been fairly common, as Henry VIII tried to outlaw it[xv].

The forms, introspective of the sleeves

and necklines, are with separate skirts, formed of many trapezoids, and

gathered in small pleats at the waist.

The other has the skirts and bodice cut in one, or else with a smooth,

ungathered waistline—presumably the skirts would have been cut wide—being

pieced, and finished with gores as needed, as they were elsewhere.

With the dress was worn a ‘kerchief’

of silk covering the shoulders and collarbone and underneath the dress, for

modesty. As may be seen in the above images, the skirts could be worn tucked into a belt, showing the lining and underdress.

Headwear: On the headwear there seems to be quite a few

regional differences—however, one of the more common written of consisted of 10

ells of fine linen rolled into wreathes[xvi]

or myter[11]

(Limerick?). Another says that it

appears like a turban, but flatter on top, much like a cheese mold with a hole

cut in it for the head (Connaught?). It

seems to have used something like 13 yards of 20 inch wide fabric. A kercheif may very well be another option (Thomond?).[12]

Writing in

1618, Thomas Gainsford says differently “They wear linen rowels about their

heads of divers fashions: in Ulster carelessly wound about: In Conacht like

Bishop’s mitres, a very stately attire, and once prohibited by statute: in

Munster resembling a thick Cheshire Cheese.”[xvii]

Jewelry: There are numerous mentions of the ladies

wearing gaudy bracelets, rings, and chains.

In addition, in the Dutch watercolour painting, you may see a necklace

(or carcanet) with an equal armed crucifix.

Observations on the Women’s Clothing

in Derrick’s Images of Ireland

There

are very few (two) images of women in Images of Ireland. These are in the Dinner with the Chief of Mac

Sweynes, and Burning of the Farmhouse plates.

Liene: Again,

bagpipe sleeves. These may or may not be

elbow length—it is hard to tell with only one example (in the other, she is

covered with a Brat). Mid-calf in length

at the most.

Gown: I am not sure what I am looking at here. Tight “Irish”

sleeves (with the opening for the leine sleeve to fall through), and a roll

collar. The collar appears the same as

the men’s, but not nearly so low. The

front closure appears to be by lacing.

The dress is mid-calf in length, and has more pleats towards the back

than the front.

Headwear: The two

examples of the headwear are both of the “cheeseroll” type, with a veil passing

under the chin.

Recreating

the Garments

Your fabric choices are almost

entirely linen and wool. My suggestions

are to use a fairly tightly woven mid-heavyweight linen, maybe 8oz or so, in

either white or saffron yellow. Saffron

yellow in this case is a pure, bright yellow of various shades, not tinged by

other colours. Based on imported

quantities, the prevalence of new saffron dyed material most likely underwent a

decline after 1560. Lower class—possibly

a natural coloured linen. For the

ladies, I would suggest a linen of a lighter weight, especially if being worn

under a gown, in the same colours. The linen

for either should, however, drape well—no stiff canvas (or if it is, beat on it

or wash a number of times to soften).

The inar could be made out of a wool

tweed (as was the one extant example), especially if portraying a lower

class. For a richer portrayal, I believe

that a boiled wool, such as that used in rug hooking would be appropriate. On the colours, bright, light colours are

good—although on the extant examples they are all shades of bog trash brown. Orchil (a moss derived purple {or bluish and

violet} dye) was available and used, with up to 5,872 pounds being imported (in

1550) in a single year[xviii]. Brazilwood (red), indigo (blue), and logwood

(blues and purples…and black) dyes also entered Irish trade during the 16th

century.

Trius—if worn—should again be a

tightly woven wool, often in a 2/2 twill and with the option of a simple plaid.

For the brat, a heavy tweed for lower

class (or working wear), or a heavy weight coating with a smooth surface such

as a broadcloth. The same colours as the

inar are applicable—there are no mentions of plaid being used, however, as it

seems to be a very Scottish phenomenon.

The fringe should be wool or silk yarns (not very common, and probably

not the best choice), either the same color as the main body or a different

one.

My

suggestion for the broges is to use the Lucas Type Irish shoes, when

reproducing them (the Dungiven outfit included a pair of Lucas Type 5 in the

find). Barefoot was also a fairly common

option, if we are to believe the illustrations—remember that the general rule

is barefoot, barelegged.

Lady’s gowns should be some form of

smooth, tightly woven wool, in bright, solid colours, much the same as the inar. A medium weight flannel type would be good, I

believe—although I would assume a heavier weight for an outer gown lined with

fur (Dutch watercolour again). I would

assume that for a lower class portrayal a tweed such as that for the men’s inar

would be appropriate.

As for a Anglicized Irish portrayal;

English Doublet (or kirtle for women), and pants (or tight trius), and hat

(semi-optional for me. Either English or

Irish for Ladies)—and wear the Brat.

Figure that the styles could be many, many years out of date—50 years,

even.

My Documentations on Irish Dress Projects

Some Additional Images

|

| Speed's Map. 1610 |

|

| Lucas de Heere. page 80 |

|

| Lucas de Heere, page 79 |

Extant Garments Found from this Period

Killery,

County Sligo; In 1824 a suite of clothing consisting of a

jacket, trius, and mantle were found only six feet under the surface of a

bog. All of the garments were formed of

a rough woolen twill, much like ‘Harris tweed’, and were shades of Bog trash

brown in coloration. We do not actually

know when this set of clothing dates from—McClintock dates it to the 15th—16th

century, based on the fact that the sleeves have the open bottoms, and must

have been worn with the wide sleeved leine. However, the overall form--the long, wide skirts, and the angular sleeves look something like late 17th century coats. Until the find is carbon dated, we can't know.

The jacket had 14/15 cloth buttons up

the front and a collar that was probably supposed to stand upright. The overall length was 43 inches, about two

feet of which was the skirt. While the

skirts of this jacket were not pleated like those on the more typical Irish

inar, it was heavily gored, making the bottom hem something like eight feet in

circumference. The sleeves are in two

pieces joined with an angular seam at the elbow, creating a permanent bend in

the sleeve, and are open along the bottom seam.

There are twelve small buttons on the outer side of this opening so that

it might be closed if the wearer wishes.

The purpose of this is “obviously” the adaptation to allow the full

sleeves of the leine to fall through.

The garment was either unlined, or had a linen lining which did not

survive.

The trius consist of two parts—a

baglike uppers, cut rather full, made of a light brown (after being in a bog)

wool; the bottoms being chequered and shaped fairly close, much like the

earlier medieval chausses, and having the point inset into the uppers. The lowers were also cut on the bias and the

seam runs down the back of the leg.

These pants are said to resemble the ones found in Kilcommon[xix].

The brat found with this outfit was

semi-circular, measuring nine feet on the straight edge, and four feet wide at

the center.

Shinrone,

County Tipperary

Dungiven

Outfit[xx]: In 1956 a farmer found a suit of cloths while

digging in a peat bog. Found were a

cloak, jacket, trius, as well as a leather belt and shoes. Both the doublet and the trius were heavily

patched (on the inside, in the doublet’s case)—the trius had some six layers of

patches in some places.

The Dungiven jacket appears very

similar to other English doublets of the late 16th century. There are a couple of unique things to it,

however—the main one is that the body of the garment was constructed with a single

piece of wool fabric, and the selvages run horizontally. It has a two inch tall collar, small wings on

the shoulders, and just about every seam (exception of the arms) has a line of

pinked piping sewn into it. The doubled

skirts consist of two lengths of fabric—one about double the width of the other

(pinked on the hemmed edges), and there is a small (four inch) gore inset into

the center back to provide the fullness to fit over the hips. The front the doublet is closed with 18 or 19

cloth buttons, and the sleeves consist of a main piece with the seam running

down the back of the arm, and a somewhat bell-like cuff.

The actual date of the doublet is

unknown—it have been made from any time between 1570s to the 1640s. In 1644, a French Traveler wrote that the

“Wild Irish” wearing a small blue cap covering the head and ears, a jacket

with a long body and four skirts, and breeches are a pantaloon…(etc.)”[xxi]. However, if you look in Derrick’s Images of Ireland[13]—specifically

the plate depicting The Chief of Mac Sweynes at Dinner[xxii],

you can see he is wearing a doublet with some similarities: High collar,

shoulder wings, longer skirts (mid thigh), which are possibly in four pieces[14]

The trius in this find are an

exceedingly well tailored and (probably) close fitting garment. They were sewn of a fine 2/2 twill tartan in

a pattern which is astonishingly complex to my eyes—being made of three

irregularly shaped geometric shapes per leg, and a stirrup strap running under

the foot. They were sewn in running or backstitch with linen

thread.

Interestingly,

the plaid that the pants are woven in has been reconstructed, and is now

modernly known as the Ulster Tartan.

The cloak is a heavily fulled 2/2

twill, and made of three pieces of material—two full width (22 inches) and a

scrap to complete the semi-circle. It is

roughly one hundred and two inches on the straight edge, and forty-eight in the

center back.

On the belt and shoes in this find,

the belt was found casing on the trius, and consisted of two fragments. The shoes are noted as being Lucas Type 5s,

with a separate sole, sewn on with wool thread.

Kilcommon

Find: The Kilcommon find consists of an inar and

trius, found in a bog (County

Tipperary

The ionar was sewn of a wool in a

coarse tabby weave and fairly well corresponds with our illustrations of the

garment—a short jacket, with an even shorter pleated skirt, and sleeves

consisting of a strip of material fastened at the wrist.

The trius consist of a one piece

uppers, formed of a 28 inch length of material folded and sewn on the left

side. The bottoms of the legs appear to

be much like the medieval chausses, with the point inset into a slit in the

uppers. At ankle level there is a row of

seven buttons shaping the area—allowing you a close fitting calf, while still

being able to remove your foot. They did

originally have feet, although these mostly did not survive beyond the top.

Bibliography:

H.F.

McClintock, Old Irish and Highland Dress: with notes of the Isle of Man.

http://www.lib.ed.ac.uk/about/bgallery/Gallery/researchcoll/ireland.html Derrick’s Image of Ireland

http://www.bristol.ac.uk/Depts/History/Maritime/Sources/2011phdflavin.pdf

Consumption and Material Culture in Sixteenth-Century Ireland. Susan Flav

http://www.reconstructinghistory.com/articles/irish-articles/the-kilcommon-costume-a-16thc-irish-kerns-clothes.html

The Kilcommon costume, Reconstructing History.

http://www.reconstructinghistory.com/articles/irish-articles/the-shinrone-gown-an-irish-dress-from-the-elizabethan-age.html The Shinrone gown, Reconstructing History.

http://www.reconstructinghistory.com/articles/irish-articles/the-dungiven-costume-a-16thc-anglo-irish-mans-outfit.html The Dungiven Costume. I also used her expanded version of the

article, found in the purchased pattern for information. Reconstructing History.

The

Dungiven Costume. Audrey S. Henshall, Wilfred A. Seaby, A. T. Lucas, A. G.

Smith and Arnold Connor. Ulster Journal

of Archaeology, Third Series, Vol. 24/25 (1961/1962), pp. 119-142. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20627382

(saved to my computer on 6-20-2012)

http://www.reconstructinghistory.com/articles/irish-articles/a-16th-century-irish-linen-headdress.html A 16th Century Irish Linen

Headdress, Reconstructing History.

http://somebody.to/The%20Irish%20KIlt%20a%20study%20.pdf Reference to the Ulster Tartan being from the

Dungiven pants.

Oxford

English Dictionary, 1971 Compacted Edition.

http://www.english.cam.ac.uk/ceres/haphazard/extra/63-144-57-2/notes.html

Extract from Henry VIII’s laws against the Irish manner of Dress, in 1539

http://www.ucc.ie/celt/published/E620001/

A Discourse of Ireland, anno 1620. Luke Gernon

http://www.ucc.ie/celt/published/E500000-001/

A View of the Present State of Ireland (1596) Edmund Spenser

http://www.bristol.ac.uk/Depts/History/Maritime/Sources/2011phdflavin.pdf Consumption and Material Culture in 16th

Cen. Ireland. Susan Flavin.

https://www.academia.edu/2346433/A_description_of_Ireland_A.D._1618

A Description of Ireland: A.D. 1618, by Luke McInerney

http://lib.ugent.be/fulltxt/RUG01/000/794/288/BHSL-HS-2466_2009_0001_AC.pdf

Sketchbook. Lucas DeHeer (1532-1584)

Note: I used the Reconstructing

History articles prior to her making them pay-to-read (sometime around June

2014).

Photo Credits:

Thank you to the member(s) of the Elizabethan Costuming group, for sharing the two line drawings, and de Heere's sketchbook.

Inar

Illustrations: McClintock, p.34. Original in Ashmolean Museum

Photograph

of three Hats: Image from Dunlevy, via http://irishhistoricaltextiles.files.wordpress.com/2012/04/three_felt_hats.jpg

Dutch

Water color: McClintock, Front page.

Original in British Museum

Image

2 in Women’s Clothing: Bayerische StaatsBibliothek, BSB Cod.icon. 341, ca

1580-1600.

Images

3-4 in Women’s Clothing: Lucas de Heere

Woman's Hat. Lucas de Heere.

Killary

Jacket: McClintock p.23. photograph

originally from National

Museum Dublin

Shinrone Gown: http://www.renaissancefestival.com/forums/index.php?topic=19946.0. Original Source Unknown.

Kilcommon

Inar: From the appropriate

Reconstructing History page.

[1] A couple

of sources (in and just post period) talk about the Irishman practically living

in their brat.

[2] Assuming

a standard cubit of 20 inches

[3]Brat,

Bratt, Bratte: Prob. Adopted from the Old Irish Brat (cloth, especially as a

covering for the body ‘Plaid, mantle, cloak’) OED (1971 Printing)

[4]

Personally I feel that by this period the brat was generally a semi-circle or

semi-oval. However, either will work. I’m wondering if it has anything to do with

your station—after all, semi-circular you are wasting some fabric….

[5] I have made a brat of the fringed style, and

am willing to share my experiments with it. My documentation for this project may be found here (Fringed Irish Brat)

[6] I am not

a weaver. However, if you search around,

there is an article out there on weaving a shaggy cloak.

[7]

McClintock interprets these as being strips of fringed material. p.28. Looking closer at the Dutch Watercolor

painting, I believe I agree—they do look fringed. In addition I had somebody else, who had no preconceptions

as to the details, describe the trim in that particular image, and they said it

looked fringed.

[8] By

myself.

[9] There is

an article on the Orkney hood which discusses the effect of sun bleaching on

types of wool. This was one of the

results.

[10] Once

again referring to the OED. I tend to

feel the first is the one meant, as locks are mentioned in addition to the

glibs.

[11] I

believe that the Myter (or mitre) referred to in this case, is a turban. The definition was in use during this

period. Discourse, and the

OED

[12] The

locations given are discussed with the specific style of headwear in Discourse

of Ireland. However, I am unsure how

much in this category changed in the 20 years post period. Given the rate of change elsewhere in the

country, I doubt that is was all that much.

[13] While,

personally, I do not feel Derricks illustrations are accurate, primarily due to

them being propaganda; I believe it would be reasonable to take his depictions Of

English style clothing as being more accurate.

[14] There

is something there which could be a depiction of another piece—it bears some

similarity to the shoulder wings.

However, I admit this could be wishful thinking on my part.

[i]

McClintock, p.28

[ii] Statute

of the Irish Parliament (1537), 28 Henry VIII, chapter xv. 'There is [...]

nothing which doth more conteyne and keep many of [the King's] subjects of this

his said land, in a certaine savage and wilde kind and maner of living, then

the diversitie that is betwixt them in tongue, language, order, and habite,

which by the eye deceiveth the multitude, and perswadeth unto them, that they

should be as it were of sundry sorts, or rather of sundry countries, where

indeed they be wholly together one bodie, [...] His Majestie doth hereby

intimate unto all his said subjects of this land, of all degrees, that

whosoever shall, for any respect, at any time, decline from the order and purpose

of this law, touching the English tongue, habite, and order, or shall suffer

any within his family or rule to use the Irish habite, or not to use themselves

to the English tongue, his Majestie will repute them in his most noble heart as

persons that esteeme not his most dread lawes and commandements [...] wherefore

be it enacted, ordeyned, and established by authority of this present

Parliament, that no person ne persons, the King's subjects within this land

being, or hereafter to be, from and after the first day of May, which shall be

in the yeare of our Lord God a thousand five hundred thirtie nine, shall be

shorn, or shaven above the eares, or use the wearing of haire upon their heads,

like unto long lockes, called glibbes, or have or use any haire growing on

their upper lippes, called or named a crommeal, or use or weare any shirt,

smock, kerchor, bendel, neckerchour, mocket, or linnen cappe, coloured, or dyed

with saffron, ne yet use, or wear in any their shirts or smocks above seven

yards of cloth, to be measured according to the King's standard, and that also

no woman use or weare any kyrtell, or cote tucked up, or imbroydred or

garnished with silke, or couched ne layd with usker, after the Irish fashion;

and that no person or persons, of what estate, condition, or degree they be,

shall use or weare any mantles, cote or hood made after the Irish fashion; and

if any person or persons use or weare any shirt, smock, cote, hood, mantle,

kircher, bendell, neckercher, mocket, or linnen cap, contrary to the forme

above recited, that then every person so offending, shall forfeit the thing so

used or worke, and that it shall be lawfull to every the King's true subjects,

to seize the same, and further, the offendor in any of the premisses, shall

forfeit for every time so wearing the same against the forme aforesaid, such

penalties and summes of mony, as hereafter by this present act is limited and

appointed.' The Statutes at Lare, Passed in the Parliaments held in Ireland,

vol I (Dublin, 1786). The act goes on to permit horse-riders to wear native

clothing, if their safety on horseback would otherwise be risked. http://www.english.cam.ac.uk/ceres/haphazard/extra/63-144-57-2/notes.html

[iii] TI,

Issue #134. The Sixteenth Century Irish

Leine, by Kass McGann

[iv] https://www.english.cam.ac.uk/ceres/haphazard/extra/extraindex.html

(page •PRO SP 63/144/57 II)

[v] A

Discourse of Ireland, L. Gernon

[vi]

McClintock, p.92

[vii] “Noe:

all these which I have rehearsed to you, bee not Irish garmentes, but Englishe;

for the quilted leather Jacke is oulde Englishe; for yt was the proper weede of

the horseman, as you may reade in Chaucer, where he describeth Sir Thopas

apparrell and armor, when he went to fighte against the gyant, which

shecklaton, is that kinde of gilden leather with which they use to Imbroder

their Irishe Jackes.” Spenser’s View of the State of Ireland

[viii] Fynes

Moryson, quote from McClintock, p.63

[ix] Consumption

and Material Culture in 16th Cen. Ireland. p. 72

[x] Don

Francisco Cuellar—a Spaniard shipwrecked in Ireland

[xii]

McClintock, p.95-96

[xiii] They

weare theyr mantles also as well with in doors as with out. Theyr mantles are

commonly of a browne blew colour with fringe alike, but those that love to be

gallant were them of greene, redd, yellow, and other light colours, with

fringes diversifyed. An ordinary mantle is worthe 4£, those in the country

which cannot go to the price weare whyte sheets mantlewise. A Discourse of

Ireland, Luke Gernon

[xiv] “I

come to theyr apparell. About Dublin they weare the English habit, mantles

onely added thereunto, and they that goe in silkes, will weare a mantle of

country making.” A Discourse of Ireland

[xv] “…and

that also no woman use or weare any kyrtell, or cote tucked up, or imbroydred

or garnished with silke, or couched ne layd with usker”Statute of the

Irish Parliament

[xvi]

William Good, McClintock, p.57

[xviii] Consumption

and Material Culture in 16th Cen. Ireland. p. 125

[xix]

Reconstructing History, The Kilcommon Costume.

[xx]

Reconstructing History, The Dungiven Costume

[xxi] The

closest contemporary description appears to be that given by the French

traveller, de la Boullaye le Gouz, after his visit to Ireland in 1644 during

the period of the Great Rebellion. He writes of the 'Wild Irish' menfolk

wearing a small blue cap covering head and ears, a jacket with 'a long body and

four skirts' (assuming this to mean two pairs of skirts split front and back as

in the Dungiven example, and not a single skirt divided at the hips as well as

before and behind), 'and their breeches are a pantaloon of white frieze which

they call "trews" ' (frieze is wool but there is no indication of

tartan pattern). 'Their shoes which they call "brogues" are pointed,

with a single sole. For a mantle they have six ells of frieze which they wrap

round the neck, the body and the head, and they never quit this mantle (either)

to sleep, to work or to eat. Most of them have no shirts.' He goes on, 'The

Irish in the North have for clothing nothing but a pair of breeches, and a

blanket on their back, without cap, shoes or stockings.'19 . Page 130, The Dungiven Costume. Henshall, Audrey S.

[xxii] http://www.lib.ed.ac.uk/about/bgallery/Gallery/researchcoll/pages/bg0055_jpg.htm

. Images of Ireland

© John Frey, 2014. The Author of this work retains full copyright for this material. Permission is granted to make and distribute verbatim copies of this document for non-commercial private research or educational purposes provided the copyright notice and this permission notice are preserved on all copies.

© John Frey, 2014. The Author of this work retains full copyright for this material. Permission is granted to make and distribute verbatim copies of this document for non-commercial private research or educational purposes provided the copyright notice and this permission notice are preserved on all copies.

It came to my attention some months ago that a Lady in Drachenwald wrote another, excellent article on the subject of 16th Century Irish dress, with the goal of creating a full suit of women's clothing. Her research article may be found here.

ReplyDeletehttp://cearashionnach.wordpress.com/2011-2/research-project-16th-century-irish-attire/

Can you answer a question or two about mantles?

ReplyDeleteI can try. Most of what I know is in the article, though.

DeleteWell I am involved in living history and want to portray an English allied Irishman/Anglo Irishman fighting during the Irish wars of the late 16th c......I am thinking of having a sort of hybrid dress; mostly English garments with some native Irish touches. One thing I want is a mantle. My question ......do they all need fancy fringe? Or can it basically just resemble a blanket with perhaps fabric frayed at the edges to look like a poor mans fringe...

ReplyDeleteWell, if you look at the few text based sources from period, you can see that the characteristic of the Irish brat is the fringe--otherwise, it's just a basic cloak. That being said, in some of the images there is no fringe, but the edges appear cut or have simple dags, so that may be another option.

DeleteBefore you decide that the fringe is not possible, have you taken a look at my documentation for my late period brat? (http://matsukazesewing.blogspot.com/2014/03/16th-century-irish-brat.html) It really isn't hard to make, if you can do a backstitch.

Hi Brann, intrigued by your research which dovetails, in a strange way, with the repatriation of ancestral remains in the west of Ireland. I sent an email contact request via SCA. Le meas, ciarán

ReplyDeleteHello, Ciarán. I have received your email. Thank you for your interest, and I will respond as soon as I can. Brann.

DeleteThank you for the valuable insights!"

ReplyDelete