The Project:

This

project is a men’s cotehardie, from the 1370s.

I wanted a garment which would work equally well for outdoors (“hunting”)

and for less formal functions—not court clothing, but certainly not low class,

either. It is somewhat more modest in

length than the average for that time—however, as you can see in the German

Effigy, not everyone wore garments which showed off the majority of your legs.

Base

Sources:

I based the garment on several illustrations from the period. A couple illuminations of soldiers (or one soldier), and a German effigy. I don’t believe there actually are any finds of this kind of garment, beyond the Charles du Bloise pourpoint[i] (which is a silk gold brocade).

I based the garment on several illustrations from the period. A couple illuminations of soldiers (or one soldier), and a German effigy. I don’t believe there actually are any finds of this kind of garment, beyond the Charles du Bloise pourpoint[i] (which is a silk gold brocade).

%2BFolio%2B122R.jpg) | ||||||

| BNF Nouvelle acquisition française 15939 Miroir Historial (Vol 1) Folio 122r |

|

Garment

Description:

This garment is a cotte or

cotehardie, the second and main layer of men’s clothing in the 14th

century. Cotehardies are somewhat

short—ranging from high-knee to mid thigh in length, generally getting shorter

as the century progresses. They are

typically closely fitted (depending on personal preference, like length) and

getting closer fitting as the century progresses—at least until the sleeves

begin to loosen in the 1380s (the body still remains close and short). It is not exactly a low class garment—other

than the skills required to make something this closely fitted being somewhat specialized, close fitting garments

by their nature waste fabric. It appears

that they were at least occasionally quilted.

|

|

Men’s cottehardies typically

feature large quantities of buttons—the main source of decoration, other than

perhaps a luxurious silk brocade being used for the garment. In general, cottes would button all the way

down the front, as well as on the sleeves (sometimes up past the elbows[ii]!),

although examples of non-buttoning sleeves are evident in artwork (however, I

cannot discard the possibility that the artist simply chose to leave them off,

or that they are just not visible due to the angle).

Construction/Pattern:

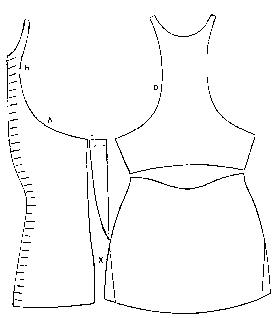

The pattern is deceptively simple,

since I decided to not use the Charles de Blois (CdB). There is

essentially a back piece, two fronts, and the one piece sleeves (with a gusset

in the back). That is it; no gores. All the shaping is at the side seams and

front opening.

|

| Charles de Blois Body. From Here. |

Even though I chose not to use the

CbD pattern, I did use it as the basis, simplifying it and eliminating the Grande

aissette sleeve style. Not only is

the majority of the narrowing for the waist at the side seam, but it is at the

back-side seam—the front-side seam is straight, at least until it begins to

flare out. The front edges curve out at

the chest, in at the waist, and then slants out slightly to the hem.

My

Goals:

My goal in this was to make a

garment to my taste which uses all (almost all) period correct material, and

the period correct methods of construction.

I was also trying to get fairly close to the inspiration images. I chose this style because I have actually

always wanted an outfit from this period—I think it looks good on me. I originally was trying to make this for the

Historical Sew Monthly Blue Challenge, back in

January…obviously, I did not succeed, but determined that it could work for the

War and Peace challenge as well, since one of my documentation pictures is of a

soldier.

Materials:

The main fabric is a 100% wool,

twill woven, flannel—the fabric is left over from my “Viking” poofy pants, in

fact (which I made several years ago, and have been saving the fabric for this

project). The fabric has been somewhat

fulled by washing. Lining is a medium

weight 100% linen, tabby woven. It seems

to me that the majority of the garments from this period (at least in Northern

Europe, where my interests are) are made of wool, and so that is the best

option. General consensus of the

Re-enacting community is that cottes need to be lined in a less stretchy

material—which would be usually be linen—to prevent distortion. Theoretically, a fabric which is far denser

would hold up without the lining; my material sadly does not quality.

The threads are where I fail. The majority of the construction is a

bleached white cotton thread—the period would be linen. The buttonholes and finish work should have

been stitched in a dyed silk thread—again, I chose cotton.

The main reason is availability—linen

and silk threads are not available in my town.

I could have ordered them online, but chose not to for my own

reasons. In addition, I really dislike

doing plain sewing with linen thread—I’ve found it breaks far too often, even

when heavily waxed; after being sewn, it is also nearly indistinguishable from

the cotton of the same shade. I do admit that a top quality linen thread probably would not have the breakage issues.

Seams:

The majority of the construction

was with a fine running (or technically, stab stitch, which I prefer)

stitch. In certain areas—the elbows and

around the armscye, mostly—I used a fine backstitch for strength. Both stitches are common to the period,

although theoretically in the case of the back stitch.[iii] The seam allowances were then felled to

either side with a whip-stitch going only through the linen flatlining, thus

encasing the linen, which easily frays.

The exception is the seam up the

back of the sleeve—in that case, the seam allowance is graded, and felled in

one direction (towards the top), and I turned the linen (which was on top of

the layers) and felled it separately.

For the first part, there is documentation in WitE[iv],

but the method for finishing the linen separately is my own.

|

| Stab stitched then felled. Ignore the basting stitches. |

The neckline and cuffs are bound,

in the same wool as the shell. Evidence

of bound edges is somewhat inconclusive, and not particularly common, but does

exist[v]. I chose to do this primarily because I did

not leave enough of a seam allowance to turn it under and use a facing.

The front and sleeve facings are

linen, and are there to provide a extra layer to help stiffen the

openings. I stitched them on with a fine

stab stitch on the outside (both the wool and linen turned under), and an

overcast stitch on the inside.

In surviving period example of

facings (often the only recognizable part), the facing is often (but not always) a fine

silk. I chose not to, not because I

don’t have a silk which would work, but because that fabric is earmarked for

another project.

|

| Front facing. The puckering is due to using a straight strip (there is no evidence of bias cut facings) on a curve. |

It now occurs to me that I should

have done a flexibility test with single turning the wool under to cover the

linen, then hemstitching that…

|

| Singling. You can't see the stitches, but can see the effect. |

Drafting

the Pattern:

As I addressed earlier, I went off

of the CdB pattern. In all, the garment

has very little ease, at least down to hip level, so drafting is fairly easy

when you know the desired shape (which I did).

In addition, I have made a CdB gambeson in the past, and so was able to

go off of that. I found that by not

including the horizontal waist seam in the back, it (other than making it

difficult to get the waist close enough) gave me ease to bend over without the

back hem riding up. I went through two

mockups for this garment.

|

| My worksheet, used to figure out the pattern before using fabric. |

It did take a couple of tries to

get the flaring and skirt circumference correct. Again, you want most of the hem to be towards

the back, otherwise it messes with the lines by causing the seam to stand out

at the sides. Likewise for the flare in the

front opening—it really needs to be almost minimal and not go out much further

than the chest curve.

|

| The front. |

Something interesting I found was

that the back shoulder seam ended up being a full half inch larger than the

front shoulder seam—this is something you do see on modern coats (handmade

ones, anyways) to provide room for your back muscles to expand and move. I began to frantically research (thoroughly

enjoying the process), searching through the images in Medieval Garments

Reconstructed (which covers the Herjolfsnes finds), and Patterns of

Fashion (which is 16th century clothing). I measured the shoulders in the majority of

the garment patterns (using the extant outline in Medieval Garments) and

found that the difference between front and back was not unknown, in either

source (in PoF it was more common on a certain type of

doublet—unfortunately I cannot remember what, did not note it down, and

currently cannot find it on my FB timeline, where I had a discussion on the

subject. I suspect it had to do with the

decorations and whether matching pattern/trim at the shoulder seam was wanted).

|

| The back, on the fold. |

The sleeves were a good bit more

difficult. I knew I wanted one piece

sleeves, which contain what I call an “elbow pocket”, and have a gusset. It also needed to have a fairly shallow cap,

to allow more movement. The other

challenge was that the hindseam needed to go over the top of the elbow, rather

than over the point (which could be uncomfortable). In part, I based my theories on the CdB, but

mainly on the G63, from the

Herjolfsnes find. Because there needed

to be an elbow pocket, the sleeve needed to be slightly wider at that point, so

I curved it out—on the underside of the sleeve.

This actually worked quite well, although I did use too much of an angle

coming down to the wrist, so the seam is slightly under the arm at that point,

rather than being where it should (over the ulna). Discussing the topic of sleeves with a co-conspirator, we came to the

conclusion that the wrist of the sleeve should be centered on the sleevehead

(assuming the hindseam is in a line with the elbow, or would be if not slightly

modified).

|

| Blue cottehardie sleeve. |

Construction:

Construction was actually fairly

simple. After drafting and testing my

mockups, then cutting the real fabrics, I basted. On every single piece, immediately after

being cut out, I basted all around the edges to keep the linen and wool

together.

Side seams were sewn, then the

shoulder seams. I then cut the sleeves

out—it is my practice to wait until it is time for them to go in, in case

modifications need to be made.

At

this point I checked the fit of the shoulder (more basting) and found that

somehow the back got widened by approximately 2-3 inches—so the shoulder seam

was not where it was supposed to be (I suspect it was due to cutting on the

fold with a springy fabric). I

discovered this when I basted the sleeves in and found them too long, even

though their measurements were correct.

The offending material was removed (after a due amount of

procraftinating), and the sleeve fitted back in. I also had to take in the side seam by ½ inch

total (on each side) because when that seam is not close enough to the body it

affects how well you can raise your arm.

Front

facings were next, followed by the sleeve facings, and binding the

neckline.

Buttons/Buttonholes:

The

most enjoyable (I am actually not being sarcastic) part was next—making the

cloth buttons. I used the standard

method[vii],

slightly modified. Rather than cutting

circles—which takes longer, and wastes fabric—I use squares. The standard method is to take your little

squares, run a circular line of running stitches around the edges, and pull the

thread to gather. You use a bodkin to

tuck the corners into the little pocket thus formed, then gather the edges

together again, and run stitching across repeatedly until they are round. The front buttons are made of 3.5cm squares

of the wool, giving a 12mm finished button size (approximately); the sleeve buttons

are from ¾ inch squares (before being trimmed of the fuzz), and gave a 7mm button size.

Based

on the London finds, the sleeve buttons are on the upper end of find sizes,

with 3-6mm[viii]

being common. My front buttons on the

other hand are average to the upper end, based on buttonhole size[ix]—however,

round buttons for the front don’t seem to have been found, just flat cloth

buttons (which are slightly to quite a bit larger). I cannot imagine how a 3mm cloth button can

be made.

|

| From Textiles and Clothing. |

Once

all the buttons were made, it was time for the buttonholes. For the front opening, I decided to use ¾

inch intervals down to the hips, then 1.25 inch intervals from there to the hem. These measurements were decided mainly by

aesthetics. The sleeve buttons are at ½

inch intervals, again for aesthetics (and because I really didn’t want to do

more)—this is conservative compared to many examples (which would have

approximately twice as many buttonholes)[x].

|

| Sleeve buttonholes. I made the sleeve buttonholes rather large, actually. This was intentional--if I made them the correct size, I might not have been able to actually button it when worn. |

|

| Front buttonholes, somewhere near the waist. |

I

followed the tutorial on Cotte Simple for construction. There are several

differences between medieval buttons, and more modern (or completely modern

ones), chiefly that there is no radial stitching on the ends, much less a

punched hole. The threads are not packed

right next to each other—there are small gaps—, and there is no evidence of bar

tacks on the ends or stitching to hold the layers in place while stitching[xi]. The last set of differences is that they seem

to be worked from the wrong side of the fabric, with the needle entering the fabric

at an angle towards the slit, which it then comes up through (and the stitch is

completed). This is based on the

observation that the visible stitches are far wider on the wrong side of the

garment.

|

| From Textiles and Clothing. |

Modern

(say, starting in the 1700s) buttonholes are worked from the right side, with

the needle being worked through the slit, then up through the fabric; the

stitches are always packed tightly with no gaps. Sometime in the Victorian era the hole was added

for the button stem. I have not yet

studied Renaissance buttonholes, so cannot speak for differences with them.

|

| For those curious. Top: 1840 Frock coat Bottom: 1750 Justaucorps |

I

stitched the buttons on after finishing the buttonholes—that task is fairly

simple; just run a thread multiple times between the bottom of the button and

the edge of the fabric, then wrap the stem.

|

| Finished front buttons. Basting threads still in place. |

|

|

The

last step was to hem, in two stages, then cleanup (removing all basting

stitches).

What

I learned:

This was actually a fun project,

however much I may have been complaining about parts of it. In the process, I learned more about buttonholes;

the whole thing with the differences between front and back shoulders. The way for making tiny buttons (that works

for me, at least)—I should experiment with how small I can make them…

What

I’d do differently:

Not much, actually. The hem is one possible major exception. The other is to pay more attention—I made a

major mistake due to…to be honest, stupidity; I will discuss this in an

appendix. I also probably should have

made the armcye slightly larger.

Now I need chausses and a plaque belt...

Now I need chausses and a plaque belt...

|

| Ah, yes. Alaskan pale--an eye blinding white... |

|

| Trying to be an effigy. |

Historical Sew Monthly

The

Challenge: April – War and Peace. This garment is from firmly in the middle of the 100 Years War, right after the first peace ended. In addition, one of my source illuminations is of a soldier.

Fabric: Wool and linen.

Pattern:

My own, based on the Charles du Blois.

Year:

1370s

Notions: Thread (embroidery floss)

How

historically accurate is it?: 96% or so.

As said above, the fabrics, methods of construction, and (theoretically)

pattern are period correct. The threads,

on the other hand, are not.

Hours

to complete: 71 hours, 45 minutes. This does not include drafting and mockups.

First

worn: Not yet.

Total

cost: Maybe 40-50 US dollars? The wool was from my stash and cost 10-15$ a

yard (I think). 3 yards of linen at 5$ a yard was purchased specifically for

this project.

Bibliography:

Crowfoot, Elizabeth; Pritchard, Frances; Staniland, Kay.

Textiles and Clothing 1150-1450. Boydell Press, revised edition (2004). Abbreviation: Textiles

Ostergard,

Else. Woven into the Earth.

Aarhus University Press, 2nd edition (2009). Abbreviation: WitE

Fransen,

Lilli; Norgaard, Anna; Ostergard, Else. Medieval

Garments Reconstructed. Aarhus

University Press, (2011). Abbreviation: Recon

Arnold,

Janet. Patterns of Fashion 3.

Quite Specific Media Group, Ltd (1985).

Abbreviation: PoF

Tremayne,

Merouda. 14th Century Garment

Construction Techniques. https://medievaltailor.files.wordpress.com/2012/10/sewing-techniques-paper1.pdf

[Accessed 4-30-15]. Abbreviation: Garment Construction

Carlson,

Jennifer L. Sewing Stitches Used in

Medieval Clothing. http://www.personal.utulsa.edu/~marc-carlson/cloth/stitches.htm

[accessed 4-30-15]. Abbreviation:

Stitches

Kelly,

Tasha Dandelion. How to Sew a

Medieval Buttonhole. http://cottesimple.com/tutorials/how-to-sew-medieval-buttonhole/

[accessed 4-30-15]. Abbreviation:

Buttonhole

Kelly,

Tasha Dandelion. Articles

(articles on the Charles de Blois). http://cottesimple.com/articles/

[Accessed 4-30-15]. Abbreviation: Kelly

CbD

Unknown. Pourpoint of Charles de Blois. http://www.forest.gen.nz/Medieval/articles/garments/Charles_blois/Charles_blois.html

[accessed 4-30-15]. Abbreviation: CdB

Pourpoint

Museum page for the Charles de Blois

http://www.culture.gouv.fr/public/mistral/joconde_fr?ACTION=CHERCHER&FIELD_98=TECH&VALUE_98=baudruche%20&DOM=All&REL_SPECIFIC=3. [Accessed 4-30-15]

[i] Kelly

CbD

[ii] CdB Pourpoint

[iii] Textiles (pp. 156)

[iv] WitE

(pp.98)

[v] Textiles

(pp. 158)

[vi] WitE

(pp. 99)

[vii] Garment

construction (pp. 3)

[viii] Textiles

(pp. 172)

[ix] Textiles

(pp. 171)

[x] Textiles

(pp. 168)

[xi] Textiles

(pp. 170)

Appendix One: Mistake

I made a serious mistake at one

point—one which put me behind by 7.5 hours of work. I sewed the sleeve buttonholes on the wrong

side of the sleeve (the bottom seam, rather than the top). Naturally, this was not discovered until I

began stitching the buttons on.

My

solution was to remove the strip containing the buttonholes, and patch it. After cutting the portion out, and cutting my

layer of wool and two of linen (one was the facing), I stitched the turn for

the facing. Next was to sew the entire

strip in place and turn, fell the seam, and then hemstitch the new facing in

place.

The last step is something I later

found out is called Rantering the Seam. I cannot document this to period, but here is

the process. Basically, after patching,

use a blind stitch or whip stitch to bring the top fibres of the fabric

together over the seam. Moisten the

surface and tease the fabric to raise the nap, then felt the fibres together

over the seam (make sure your hands are completely clean…). The last step is to shave the nap, once the

fabric is dry.

|

| Excised. |

|

| Forming the piece which will be inserted. When handsewing, I work away from me, and use a bottle as a weight to put some tension on the fabric. |

|

| All sewn in. |

|

| Rantering the seam. |

|

| Teased. I don't seam to have one of it after felting/shaving. |

©

John Frey, 2015. The Author of this work retains full copyright for this

material. Permission is granted to make and distribute verbatim copies of this

document for non-commercial private research or educational purposes provided

the copyright notice and this permission notice are preserved on all

copies. Photographs of my work may not

be duplicated.

No comments:

Post a Comment